I haven’t shared anything here since April. I think I became overwhelmed by the interconnectedness of everything, and felt that I couldn’t write about one thing without having to write about ten other related things, and situate it all in the context of what is happening in the world right now. The truth is that writing doesn’t have rules like this — they were rules I was imposing on myself, and they led me to feel like I didn’t want to share anything I was creating.

For me, the end of August is a bit like New Year’s Eve — an opportunity for reflection and reassessment, before we slowly sink back into winter. I found I wanted to spend time putting something together. So here’s something I’ve formed out of twelve phone notes and some things I scribbled on envelopes over the last four months.

Some names have been abbreviated for anonymity.

April in London

I am sitting with my parents and my brother in a basement restaurant celebrating my mother’s birthday. Behind us are an older man and a younger woman who I am watching out of the corner of my eye in the mirror. The woman has red hair and is about my age, and she is talking about her current relationship.

“We’re at very different places in life,” she tells the man, who I assume is her father, carefully. “But he makes me laugh. Every night I’m sobbing with laughter.”

“That’s good,” her father says encouragingly.

“Anyway, my next relationship certainly won’t be with a man,” she adds.

“I see,” he says. Their food arrives. They both eat in silence for a while.

“Something I discussed in therapy is that my relationship with you has to change,” she tells him, abruptly.

He responds something monosyllabic, lost in the sound of clattering cutlery.

“I don’t like seeing you upset,” she says, in the same cool, level tone she has been using since they sat down. She is puppeteering a hollowed-out langoustine, holding it up by its claws and making it do a dance macabre around the edge of the plate. “I’m going to the bathroom.”

She gets up and leaves, and her father is alone at the table. He downs the rest of his wine, and sits back, hands on his stomach, forlorn rather than sated. The waiter comes to offer him the bill, and he looks relieved, becomes jovial.

As he pays, the woman sits down again, and stares at me in the mirror.

“She looks like someone you would know,” my father says.

May in London

I’m at a party, recounting a terrible situation I’ve found myself in to A. I didn’t expect him to be particularly sympathetic about it, but he is. Later, a spiced rum and coke travels across the crowd and is pressed into my hands. I catch A’s eye as he French exits, and he grins at me. It feels like the nicest thing he could have done in that moment. I’m touched that he remembered.

On the way home from the party, which has made me feel a bit like I’ve been turned inside out, I’m standing over C on the Overground beside a woman I just met, who is telling me about her fear of spiders. I must be exuding some kind of nervous energy because C is telling me repeatedly that she has faith in me, while looking up at me from her seat.

It has been a difficult spring, full of shocks. More reminders (as if I needed them) that everything is fleeting; that the greatest joys can end up being the greatest losses. I haven’t melted into the summer, as I usually do, but rather feel thrust into it somewhat unwillingly. Some of the pain is sharper, some duller.

The tables on the rooftop at the Joiners Arms have been painted and I can’t find number 35 anymore. Tamzyn and I always said we were going to get ‘35’ tattoos after that table. Maybe we still will, even if we can never find it again. I find the Three of Hearts card on the steps down into the Finchley Road underpass, a significant place for it to be. Google tells me it’s the karma card. Apparently, I may try to avoid responsibility and live just for the moment. I should learn not to spread myself too thin, a natural trap I could fall into.

Lily tries to sell her old jeans at SET Market. She drapes them over the top of a leather bench by the pool table, but they have so many extra zips and pockets that they’re too heavy and they slither down. She lays them out horizontal instead. They are napping, on a Sunday afternoon. I do a bibliomancy reading for her from my book and we land on a blank page that just says ‘May’, which we can’t argue with.

I receive an email that says, ‘1088 days since your last eye test… and counting.’

I practise the art of spotting strange old signs in small towns. Of coaxing slugs out of lettuce leaves to release them in the garden and not eat them in the salad. Of telling childhood stories about my younger brother which make him squirm, at dinner parties where we mostly serve lentils or hummus.

Pressed against the windows of the new build flats by the railway tracks are bicycles, pillows, Deliveroo delivery bags, and washing racks by open windows. It looks like all of us are trying to escape the black mould. Sometimes I wonder if black mould is the one thing which unites everyone in this city.

I pick Tuuli up from uni and walk her home, which feels like the most convivial thing one could possibly do. We drink out of tiny bottles across the river from the Tate Modern and talk about gender. Turns out we’re both pissed off. Francesca Woodman, Joan Didion, what’s in my girl bag, yearning and longing, i’m literally just a girl, girlhood is just lay in bed and rot. The sunset reflects off the Shard, an almost full moon faint right above its point, and I think maybe I do love this city.

June in London

I’m sitting with the windows wide open

trying to inhale fresh air

,without making much effort

The very beginning of an email from my grandmother, visible in my inbox. Opening it doesn’t provide any further context or clarification. Without making much effort to inhale fresh air? Doesn’t the trying imply some effort? I sort of know what she means though. Trying to inhale fresh air, without making much effort. Ambivalence.

The older women I see on Thursday afternoons at my dance class are always cold. They wear jeans and cardigans and some of them even wear fingerless gloves. In June. When we hold hands for partner dances my hands are vaguely sweaty, theirs cool as marble. Most of them make quite good eye contact. They remain perplexed by my presence.

“Do you match your clothes to your hair or your hair to your clothes? Because you’re very russet,” Anita, who is 80, tells me.

“You have to laugh or you’ll cry,” says Noleen, who is Irish and is missing all her front teeth, but has the most contagious smile.

There’s comfort in thinking about being older when the stuff of youth becomes turbulent. May was such a horrible month. It was my friends in their sixties and seventies who got me through it, with equal parts earnest wisdom and stories that were so much worse than mine that I had to stop feeling sorry for myself immediately.

Ruby and I go to see Ethel Cain at the Roundhouse, our memorial for Ariel. We haven’t seen each other since before she died. It storms violently in the queue and we hold onto each other under Ruby’s umbrella. I down a double espresso which I’ve bought so I can use the toilet in the café opposite, and the sun comes out. I drink too much coffee and I think of you often / In a city where reality has long been forgotten / Are you afraid? 'Cause I'm terrified / But you remind me that it's such a wonderful thing to love. We are queuing across the street from where I was assaulted. My efforts to reclaim Chalk Farm Road have been futile thus far, but it feels like this just might work.

There is a boy who has come from Palestine just for this concert standing next to us inside. It is the first time he’s been to London. Ruby and I cry so hard to ‘Sun Bleached Flies’ we almost have to leave afterwards. Singing if it's meant to be then it will be / I forgive it all as it comes back to me. We’re tear-streaked and sweaty and it all feels better just for a moment.

Ruby sleeps on my sofa on a huge piece of fabric my grandmother once gave me to make a skirt. I close the door on her quietly, as one would on a sleeping child. She is gone in the morning.

June in Lewes

Everything in Lewes is bleached blue. I have such bad hay fever in the graveyard that I have to turn back before I’ve even properly read about the anchorite’s cell.

We’re talking about Brexit in SJ’s garden, because Americans can’t get enough of the nonsense of British politics. I say I remember coming downstairs on a school morning and finding my mother crying at her computer. “I remember exactly where I was,” C says. “I was in Deep Shock.”

The six of us carry musical instruments down a hill and through the town’s crooked little passages. In the pub, I’m the youngest at the poetry reading by about thirty years. Everybody says the bartender is rude, but I believe I might have charmed him by bringing him all the empty glasses and constantly, apologetically, asking for his chalk pen. I sit on a sack on the floor, because these days I have been reminding myself that I have free will and that means that I don’t actually have to sit on a chair. Kim and Danny unite their words and music in soaring, lonely ballads which tell of the desert and rattlesnakes and a field of lightning. Kim reads one of my favourite poems of hers, the one about eating with her friend, who is dying, and they both know it but they don’t talk about it. I know my friend is going, / though she still sits there / across from me in the restaurant, / and leans over the table to dip / her bread in the oil on my plate.

I record it in my voice memos and forget to turn it off so that later, when I’m out on the terrace smoking a joint with a radio host I’d cornered to ask for a cigarette, he points out that I’ve been recording our whole conversation accidentally. It’s okay, because we were only talking about the swallows nesting in the roof across the road.

July in London

These days, I can only write on the bus, and the only song I want to listen to is ‘Rooms on Fire’ by Stevie Nicks. Well, there is magic all around you / If I do say so myself / Well, I have known this much longer than I've known you. I think Stevie wrote it as a love song. I’m listening to it as a departure, with defiance. In spite of it all, there is magic.

All my compulsive tendencies are much more present. So is my sense of inadequacy. And, unusually, anger.

the typing device has turned into a cape shop

everything has turned into a vape shop

I write this in my phone notes while crossing the road in East London on my way to get a tattoo of a mermaid. Actually I write ‘the typing service has turned into a vape shop’, but my phone has taken to behaving as if someone else is controlling it remotely. Either way, it doesn’t feel like the typing service which has turned into a cape shop is worth much more of anyone’s time.

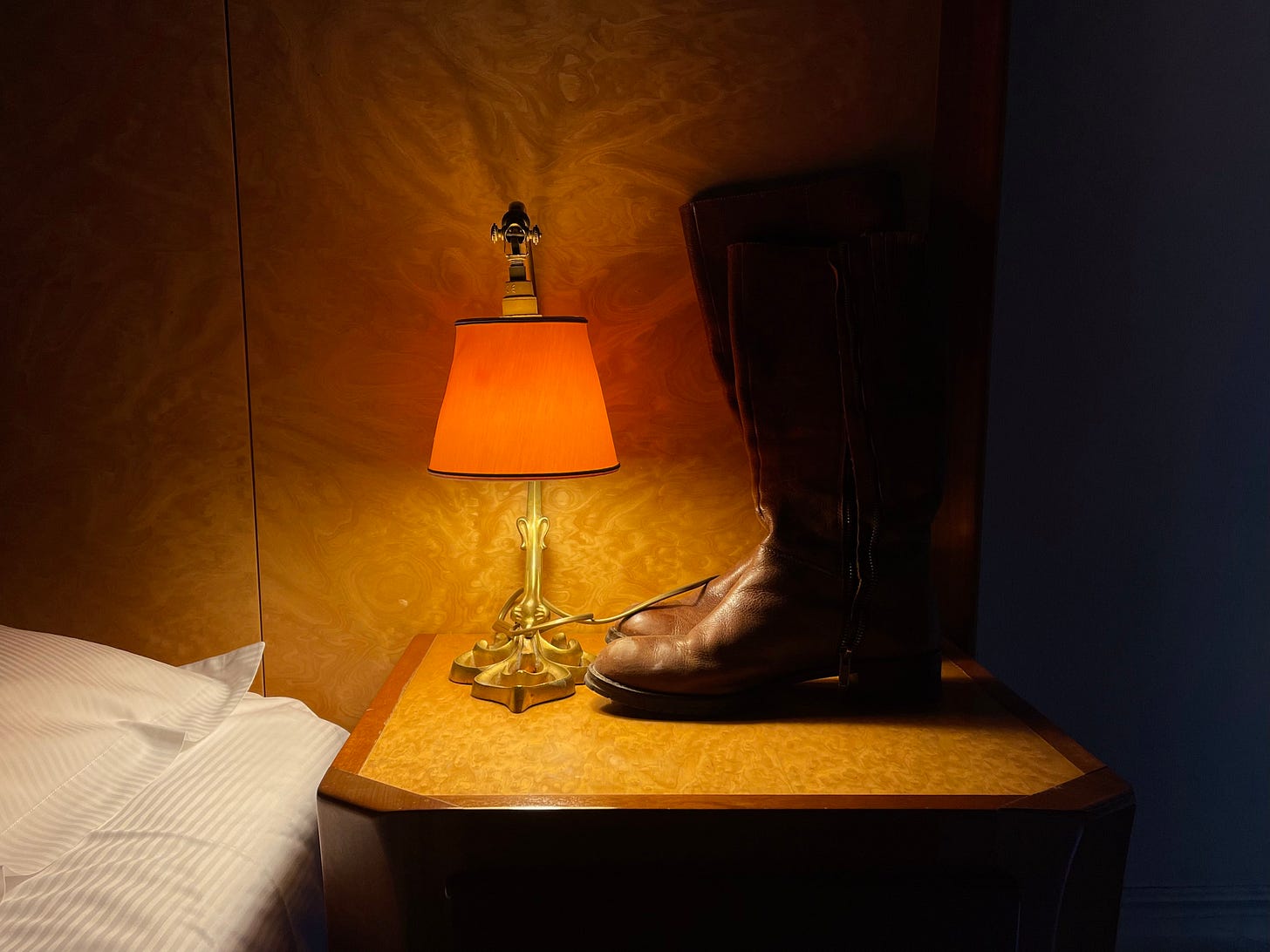

August in France

I drop the end of the bread on the grass where I sit. I’m leaving traces like Gretel; taking this bread and everything which makes it up from its source to somewhere new. We are crossing the whole country, and the only signs that we were here are the red stains my hair has left on motel towels. On the side of the road, by the hole-in-the-floor toilet, a tourist board tells of a beast which reigned here during the Middle Ages, leaving dozens of casualties. Nobody could ever be sure that it wasn’t just a man.

I’m always in a more heightened state of emotion when I’m here, which I think is a good thing. That’s not to say that I’m usually apathetic, but in London I don’t feel the same impulses that I do here. The urge to cry at a beautiful song, or a line in a book, or a thought that strikes me as we swoop around one of the blind bends on the mountain roads.

I notice things more here too. Like now, the two brown lines across both of my feet where I’ve tanned between the straps of my sandals. The way the little silver fish earring H gave me this morning, which someone must have lost here, gently knocks against my neck, attached to my own hoop earring. The beauty of Jeffrey Eugenides’ writing; the way the words feel crisp and distinct, like bricks set into place, each one exactly right. The small river snail which has attached itself to the glass bottle I hold under the water with my foot.

This morning I had a glimpse of one of my many potential alternative realities, at the ‘Introduction to Fishing’ for children in the neighbouring village. S queued up to write their names on a piece of paper, on a plastic table laden with metal trays of fried eggs drowning in grease and nondescript pieces of greying meat. They were handed camo T-shirts with the name of the fishing club printed on the front and back and dark green caps, and then sent to the riverbank with rusting fishing rods, where they promptly dropped their caps in the water.

The man helping them pierce pieces of sweetcorn with fishhooks (so fine and pointed it made me wince to look at them) was huge and muscular, his hair buzzed to a few centimetres long. He had the air of an American footballer, and yet he seemed soft. He kept looking at me then quickly looking away, as if burnt, as I stood ankle-deep in the lukewarm water which was curdled with fish blood. I looked at his enormous hands casting the fishing lines for the children with savage grace and imagined them around my waist, and it didn’t disgust me. A truck pulled up, churning up dust, and a bunch of men hopped out with a boombox blaring electronic music in homage to wild boar. I took in his silent carefulness, his somewhat brutish half-smile.

At the end of the gathering, after little girls in pink tutus had caught most of the fish farm trout which had been rounded up and dumped in this enclosed part of the river, and the American footballer had banged their heads against the rocks until their jaws hung slackly open and their gills oozed deep red, they wound back the chicken wire and opened up the river again. The trays of eggs and meat were cleared and the music stopped. We left with a clear plastic bag bulging with dead fish and neither the man nor I cast any more looks at each other. I sensed a disappointment on his part, not in our lack of connection, but in me.

He finds a strange double in the woman I meet at the night market a few days later. She’s barefoot, dressed all in green, with loose long hair and a shy smile. She appears behind me as soon as I arrive and presents me with five jam jars, filled with things she’s foraged in the forest. She holds each one under my nose and tells me to breathe in deeply, and makes unwavering eye contact while I do so. I identify thyme and pine sap, but I can’t place laurel — nor would I have been able to find the word for it in French. We talk for a long time as the sun sets gold behind the mountains. She tells me that she lives alone in the forest in the house of an older man who she’s never met. We laugh a lot. She gives me incense she’s made and tells me to burn it on stone, and all of the thoughts which are flying around inside my head will dissipate. And then, abruptly, she asks me if I’ve been vaccinated. We see each other at a concert a few nights later, but our paths don’t cross.

Every day we drive past an open garage in the village. The same Singer sewing machine and rail of old clothes sit outside each day, baking in the sun.

In the tabac, I wait a long time at the counter behind an old man trying to buy a porn magazine. “They only come out every two months,” the man at the till says gently, “and you come here every day.”

One day a car stops outside the house. “I have absolutely no idea where I am,” the woman in the car says. “I’ve been driving in circles for hours.” S asks if she wants a cup of tea. She does, and she also wants to join us on our hike, but her small dog has problems with his feet and can only come if he is pushed in the enormous pushchair which she has produced from her otherwise empty car boot. We are forced to part with them.

At the summit, half-submerged in a freezing waterfall, S and I talk about relationships. “Being single when you’re older can be hard,” he tells me. “Sometimes it sends you a bit crazy. You could, for example, end up driving around in the middle-of-nowhere with your disabled dog and knocking on peoples’ doors.”

On our way down we call for our friend outside his house, but the door is locked, and he’s nowhere to be seen. I believe with almost certainty that he’s inside, in the cool dark. That night S tells me that the little tumbledown stone house down the road also belongs to him, and that if you stand in front of it and scream through the doorway it echoes across the whole valley. I imagine calling his name into it. I can almost see him appearing over the crest of the road in response, gaunt and beautiful, with one of his carved walking sticks in his hand.

The day before my 24th birthday I cycle along the valley to my favourite river beach. The cycle track used to be a train line. It’s verdantly green and every so often there are damp, black tunnels that seem to swallow you whole, taking you into the core of the mountains. The original railway bridges still stand, enormous brick arches which make you feel as though you’re passing through a cathedral.

I stop at a van selling drinks and falafel along the track and ask for water for the dog. The woman scolds me for making him run alongside me: “He’s only doing it because he’s scared you’re going to abandon him.” He’s a hunting dog, and there’s nothing he loves to do more than run.

There are about twenty tables around the van, and dreamcatchers and bunting and strange wooden structures made by valley hippies, but it’s deserted. She sends me across the road to a tiny stream where the dog can submerge himself before we ascend the next enormous hill. Here, instead of cutting through the rockface, we have to go over it. The track is punctuated with seemingly randomly placed exclamation points, images of cars swerving off roads, and a sign that says in French “important slope”.

At the river beach I see a French family who I’ve crossed paths with about six times this week already. They have a very blond baby with a mullet, who is fascinated by the dog and by me. At some point he waddles over to me and presents me with a rock.

“Is it a present for me?” I ask him. He nods solemnly.

“It’s a good choice,” his father says. “That stone is local to the region. You can paint with it.” He takes the stone from me and holds it in the water, then rubs it several times against another stone. A deep mauve paste seeps out. This is my only physical 24th birthday present. It’s a good one.

On the way back I stop at the van again. The woman gives me a glass of local white wine, and citronella against the mosquitos. A deer fly has been biting me all the way up and down the mountain track, but I was physically unable to take my hands off the handlebars to brush it off. She gives me ointment for that too. We talk for a while and I can feel her slowly warming to me. A man who I assume is her partner arrives. He is lean and tanned with white hair and he can’t stop coughing. She makes him tea. Their interaction somehow feels deeply private, so I try to involve myself in my book.

The wine loosens something in me, and all the way back along the train track I am in awe at the beauty of the valley — even more so than usual. The church spires rising out of small, dusty villages; the stone crosses in the wooded cemeteries silhouetted against the sky. I pass a very elderly couple walking hand-in-hand, who laugh at me with the dog. We do make a somewhat unlikely pair.

I expect to spend my 24th birthday entirely alone. My grandmother has wished me happy birthday via email twice already, once on the 24th of August and once on the 26th. It’s not that she’s forgotten the date of my birthday, I think, it’s that she is lost in time.

In the morning, the sun seems to take longer than usual to rise over the trees. I make a coffee with the last of the milk, using the coffee machine that S bought recently at a flea market for 10 euros. It tastes like cigarette ash and I can only conclude that something is burning deep inside the machine. I pour it down the sink and make another one, black, and take it to the bench that gets the first of the sun. The dog follows me and settles down at my feet, and the cat nudges at my legs. I’m not so alone after all.

F drives past in his van and stops to say hello as always. A woman from the village has given him six chickens, he tells me, and he has lost them already. One of them is an enormous cockerel — this big, he shows me with his hands. I’d heard a cockerel early in the morning, in my half-dreaming state, but had thought I was imagining it. When I tell him it’s my birthday he jumps out of his van and gives me two kisses. “Come and see the cockerel,” he says. “I’ll be searching for him for the next thirty minutes.” After that he’s on his own in the world, I guess.

I listen to the same songs I listened to here four years ago. The summer when Ariel, Ruby and I sent each other phone notes poetry; the summer when I met Anastasia. They have started to make sense in different ways. Everything I love is on the table / Everything I love is out to sea / I have only two emotions / Careful fear and dead devotion. I have been stirring up a lot of dust.

While I wait for the spin cycle to finish, I sit outside the house and watch the sun go down across the valley. I can hear one cicada chirping on the mint plant, which is almost dead. A couple of small birds, a hornet, a single, intermittent woodpecker. The distant rushing sound of the river below and the wind running through the branches of thousands of trees. Dry grass crackling under the cat as she stretches out. Bees in the fig tree. Single leaves falling. The hillside becoming a muted grey-green.

SONGS QUOTED IN THIS PIECE:

Patricia by Florence and the Machine

Sun Bleached Flies by Ethel Cain

Rooms on Fire by Stevie Nicks

Don’t Swallow the Cap by The National

really wonderful prose, tilda. whenever you write here next will be worth the wait

Hi! just wanted to say that I love this piece you've written :) such great extracts, the conversation with the father and daughter - really enjoyed that one.